About

I am a computational social scientist and behavioral economist with a background in mathematics and a passion for the quantitative modeling of political behavior. I obtained a Ph.D. from the Graduate School of Economic and Social Sciences (GESS) at the University of Mannheim. Methodologically, I develop and use in-silico simulation methods (e.g., agent-based modeling), which I use to study party competition and opinion dynamics. I am also interested in experimental research conducted both in the laboratory and through large-scale population-based surveys. My substantial research focuses on coalition politics and electoral behavior, especially on pre-electoral coalition politics and how it affects electoral behavior. My work has been published in leading international peer-reviewed journals like The Journal of Politics (JOP), European Journal of Political Research (EJPR), Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), Political Science Research and Methods (PSRM), and Electoral Studies.

- Agent-Based Modeling

- Causal Inference

- Experimental Research

- Coalition Politics

- Electoral Behavior

Dr. rer. soc. (Ph.D.)

Graduate School of Economic and Social Sciences, University of Mannheim

M.Sc. in Economics

University of Kiel

M.Ed. in Mathematics and Economics/Politics

University of Kiel

B.A. in Mathematics and Economics/Politics

University of Kiel

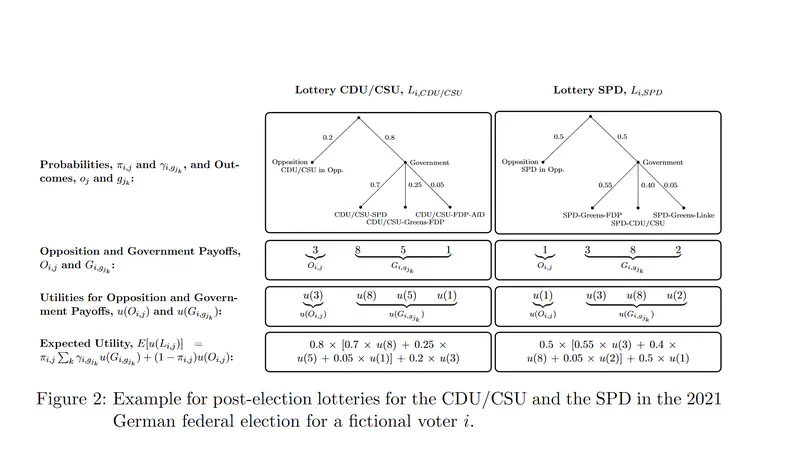

Featured Publications and Working Papers

When voters support parties in multi-party democracies, it is often uncertain what coalition government the party will join. How do voters deal with the lack of clarity in parties’ coalition government prospects? We develop a novel conceptualization of coalition-directed voting to study the effects of this type of uncertainty. We present observational and experimental evidence that supports the idea that voters are riskaverse when considering coalition government options. Observational survey analyses show that the perception of uncertain coalition prospects negatively affects the propensity to vote for such a party, even when holding the expected coalition government payoffs constant. Using a survey vignette experiment, we provide causal evidence that uncertain coalition prospects reduce the propensity to support a party, compared to certain coalition prospects given the same expected coalition government payoffs. Together, these findings provide insights for our understanding of party competition and parties’ coalition strategies.

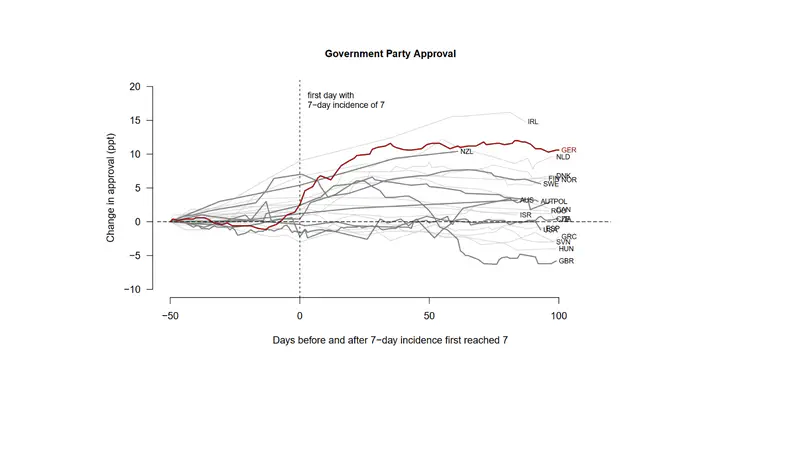

In times of crisis, citizens tend to increase their approval of the government and its leader which might shift the balance of power. This ‘rally effect’ is a persistent empirical regularity, however, the literature does not identify its underlying causal mechanisms. We argue that crises induce threat and anxiety, and theorize that perceived threat increases approval of the incumbent leader, whereas anxiety decreases it. By analyzing German panel data from the COVID-19 pandemic, we causally identify both mechanisms and provide systematic evidence supporting this theory. Moreover, we increase the scope of our theory and show that both mechanisms are also at work when citizens approve cabinet members who manage key port- folios. Finally, we also leverage a comparative survey design across eleven countries to show that our evidence generalizes beyond a single country. Our findings have highly important implications for our understanding of the rally effect and crises politics in democracies.

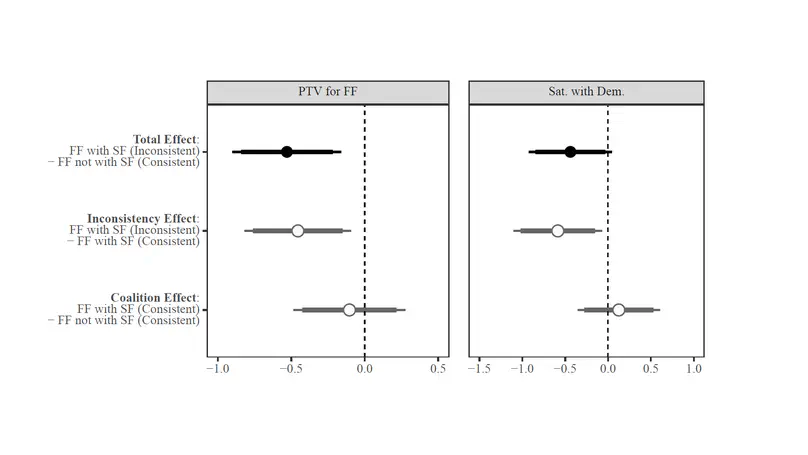

In proportional systems, parties generally signal their coalition preferences to voters during election campaigns. Breaking coalition promises after the election entails normatively undesirable repercussions for government identifiability and accountability. This study is the first to investigate voters’ short-term reactions to post-electoral coalition choices of parties in conflict with pre-electoral coalition signals. Firstly, I performed a quasi-experimental investigation that considers an instance of inconsistent coalition choice following the 1996 New Zealand election. Secondly, I conducted an innovative survey experiment during the government formation period following the 2020 Irish general election. I find that breaking coalition promises is costly not only for the inconsistent party but also for democracy in general. Inconsistencies concerning coalition choices make voters less likely to support the inconsistent parties and erode voters’ satisfaction with the way democracy works. The findings provide important implications for government identifiability and accountability in proportional systems, democratic stability, and the effectiveness of cordons sanitaires vis-à-vis radical parties.

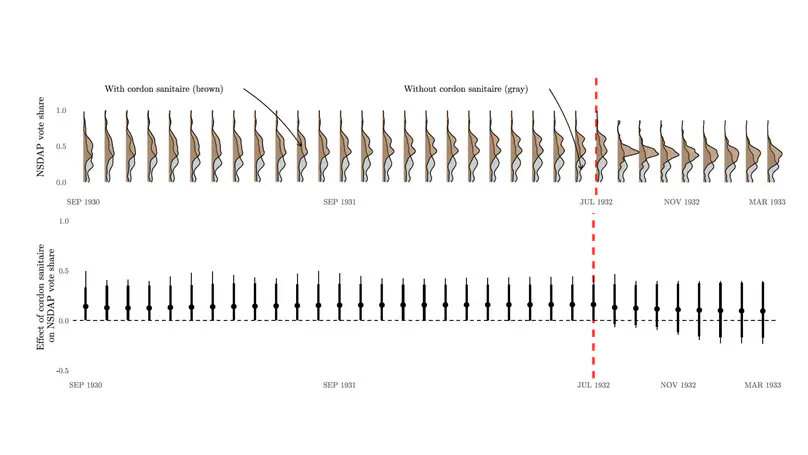

Ruling out forming coalition governments with parties critical of liberal democracy, i.e., establishing cordons sanitaires vis-à-vis these parties, is often seen as a crucial contribution to safeguarding liberal democracy. However, little is known about whether cordons sanitaires are effective in reducing the vote share of parties isolated in this way. Specifically, the effects of cordons sanitaires on voting induced by changes in voters’ expectations of post-electoral government formation remain unclear. I address this research gap by conceptualizing cordons sanitaires as a specific class of pre-electoral coalition signals and drawing on theoretical knowledge about the electoral expectation-induced consequences of coalition signals. I integrate these theoretical insights into a formal agent-based model of dynamic party competition and perform counterfactual simulations in an artificial democracy calibrated to resemble the 1930s Weimar Republic. The results show that the vote share of an artificial NSDAP increases when a cordon sanitaire is erected against it. By illustrating the theoretical possibility (not inevitability) of these unintended expectation-induced consequences, the paper provides important implications for research on the mainstream parties’ response to radical parties.

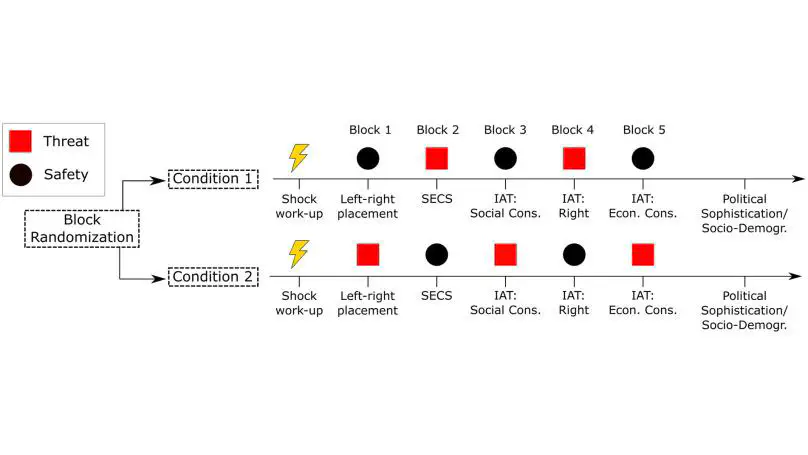

Previous research suggests that state anxiety may sway political attitudes. However, previous experimental procedures induced anxiety using political contexts (e.g., social or economic threat). In a pre-registered laboratory experiment, we set out to examine if anxiety that is unrelated to political contexts can influence political attitudes. We induced anxiety with a threat of shock paradigm, void of any political connotation. All participants were instructed that they might receive an electric stimulus during specified threat periods and none during safety periods. Participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions. Political attitudes (implicit and explicit) were assessed under safety in one condition and under threat in the other. Psychometric, as well as physiological data (skin conductance, heart rate), confirmed that anxiety was induced successfully. However, this emotional state did not alter political attitudes. In a Bayesian analytical approach, we confirmed the absence of an effect. Our results suggest that state anxiety by itself does not sway political attitudes. Previously observed effects that were attributed to anxiety may be conditional on a political context of threat.

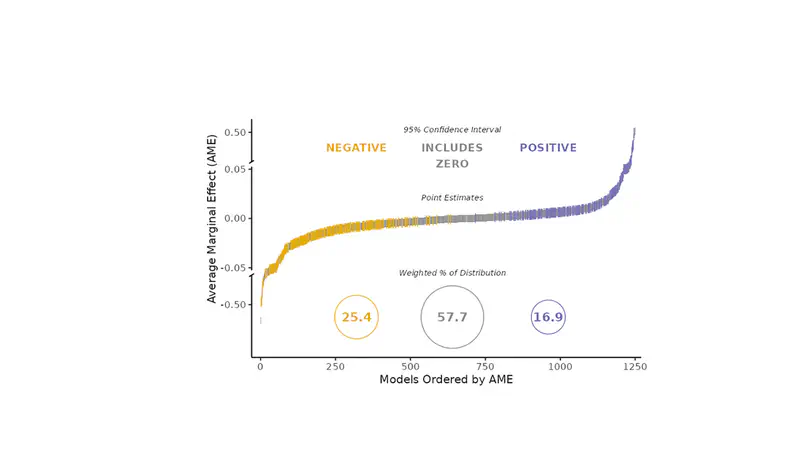

This study explores how researchers’ analytical choices affect the reliability of scientific findings. Most discussions of reliability problems in science focus on systematic biases. We broaden the lens to emphasize the idiosyncrasy of conscious and unconscious decisions that researchers make during data analysis. We coordinated 161 researchers in 73 research teams and observed their research decisions as they used the same data to independently test the same prominent social science hypothesis, namely that greater immigration reduces support for social policies among the public. In this typical case of social science research, research teams reported both widely diverging numerical findings and substantive conclusions despite identical start conditions. Researchers’ expertise, prior beliefs, and expectations barely predict the wide variation in research outcomes. More than 95% of the total variance in numerical results remains unexplained even after qualitative coding of all identifiable decisions in each team’s workflow. This reveals a universe of uncertainty that remains hidden when considering a single study in isolation. The idiosyncratic nature of how researchers’ results and conclusions varied is a previously underappreciated explanation for why many scientific hypotheses remain contested. These results call for greater epistemic humility and clarity in reporting scientific findings.

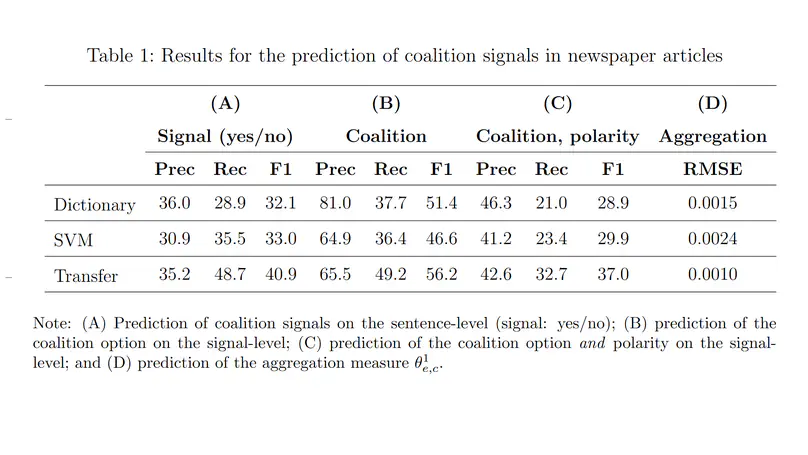

Inter-party communication is crucial in representative democracies, enabling in- formation exchange and dialogue among political parties. Despite its importance, research on this topic remains limited due to a lack of comprehensive conceptualization and challenges in large-scale measurement. This article proposes a holistic definition of inter-party communication as public communication by parties about others with a positive, neutral, or negative stance, focusing on collaboration, policy, or personal issues. To effectively measure inter-party communication, we introduce a novel transfer learning approach capable of automatically classifying large volumes of textual data. Two case studies on coalition signals in Germany and negative campaigning in Austria demonstrate its effectiveness. The study contributes to our understanding of political discourse and the dynamics of party competition. Our approach advances automatic text classification methodologies and opens new avenues for studying political communication.

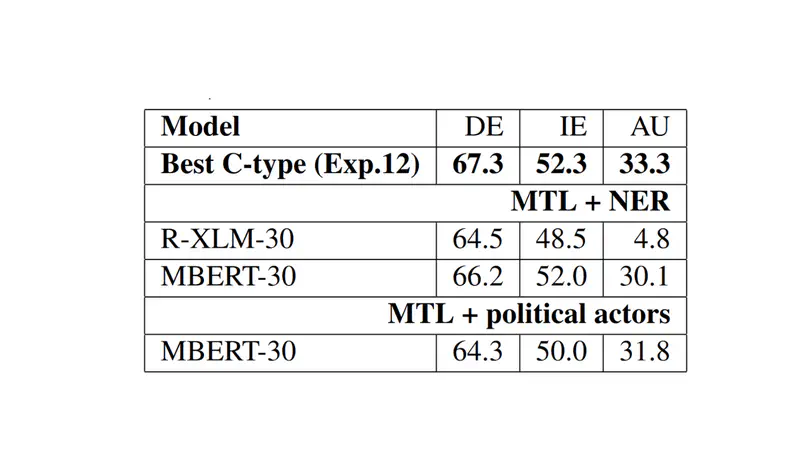

In this paper, we introduce the task of political coalition signal prediction from text, that is, the task of recognizing from the news coverage leading up to an election the (un)willingness of political parties to form a government coalition. We decompose our problem into two related, but distinct tasks, namely (i) predicting whether a reported statement from a politician or a journalist refers to a potential coalition and (ii) predicting the polarity of the signal – namely, whether the speaker is in favour of or against the coalition. For this, we explore the benefits of multi-task learning and investigate which setup and task formulation is best suited for each sub-task. We evaluate our approach, based on hand-coded newspaper articles, covering elections in three countries (Ireland, Germany, Austria) and two languages (English, German). Our results show that the multi-task learning approach can further improve results over a strong monolingual transfer learning baseline.

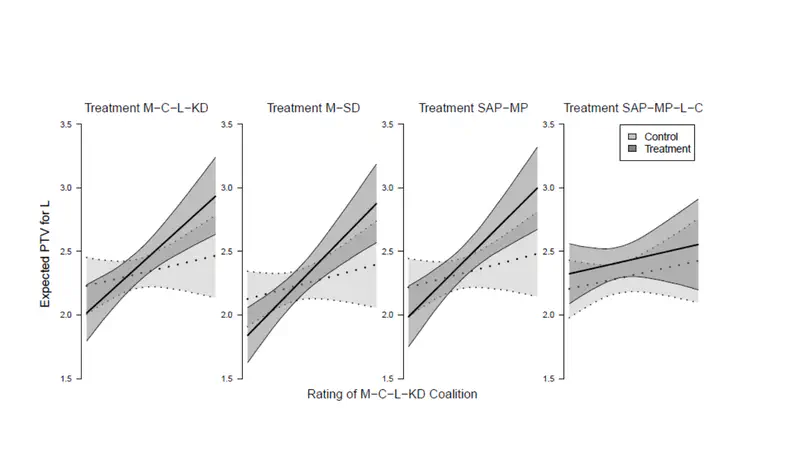

Existing empirical research suggests that there are two mechanisms through which pre-electoral coalition signals shape voting behavior. According to these, coalition signals both shift the perceived ideological positions of parties and prime coalition considerations at the cost of party considerations. The work at hand is the first to test another possibility of how coalition signals affect voting. This coalition expectation mechanism claims that coalition signals affect voting decisions by changing voters’ expectations about which coalitions are likely to form after the election. Moreover, this paper provides the first integrative overview of all three mechanisms that link coalition signals and individual voting behavior. Results from a survey experiment conducted during Sweden’s 2018 general election suggest that the coalition expectation mechanism can indeed be at work. By showing how parties’ pre-electoral coalition behavior enter a voter’s decision calculus, the paper provides important insights for the literature on strategic voting theories in proportional systems.

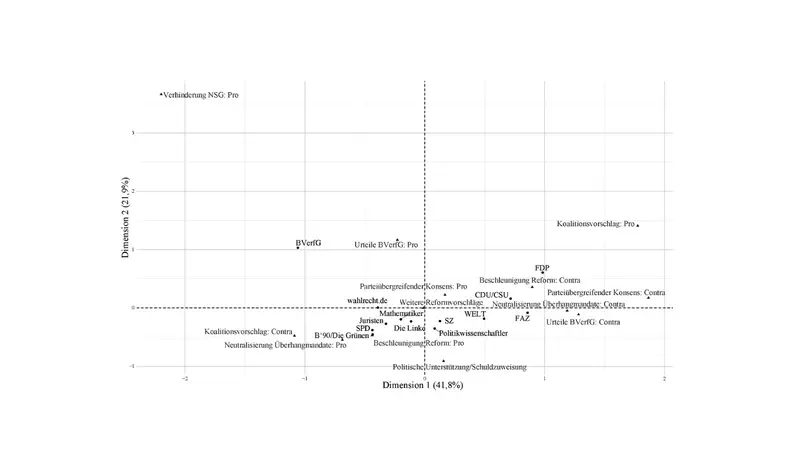

The German electoral law to the federal parliament was reformed in 2011 and in 2013. While political scientists have extensively evaluated consequences of these reforms, the role of the public discourse has been largely neglected. We analyze articles from three leading German newspapers (FAZ, SZ, Welt) on this topic and find the debate around the reforms to be dominated by parties and political institutions. Scientists, interest groups, and journalists have only played minor roles. Regarding content, the discourse largely focused on surplus seats, reform speed, and a proposal by the CDU/CSU‐FDP coalition government in 2011. A broad public debate in which multiple social groups could participate has not taken place. From a normative perspective this is problematic since the lack of a public debate might have contributed to the poor quality of the reform’s result.

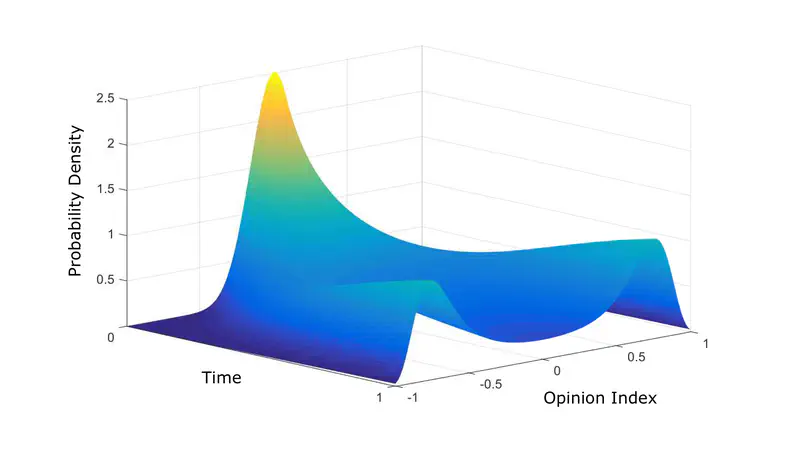

This study formulates and tests an agent-based model of opinion dynamics which claims to explain the evolution of political preferences by means of social interaction effects. The approach incorporates a majority and a momentum mechanism claiming that individuals are affected by perceived opinion levels as well as by opinion changes. This theoretical model is empirically tested by estimating its parameters on government satisfaction in Germany. The results support the empirical validity of the approach, as a significant momentum mechanism can be identified while other significant parameters display meaningful estimates. Additionally, almost every week’s level of government satisfaction is a likely realization of the process given the data of the previous week. Beyond that, the findings suggest that individuals are rather affected by opinion changes than by opinion levels and that nonconformity plays a more important role in the evolution of the considered preference than conformity.

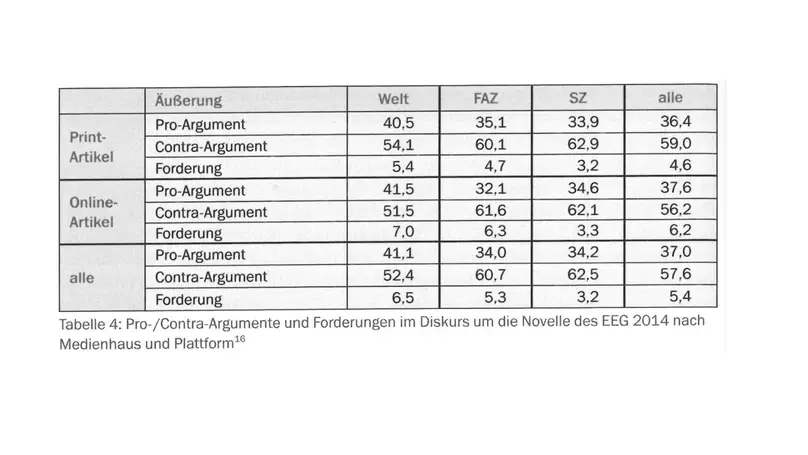

With the emergence of digital technologies, the mass media exploited new distribution channels. This differentiation of communication platforms led to a fragmentation of the public sphere. Based on a comparative discourse analysis on the German Renewable Energy Act Amendment 2014, including both print and online media, this article investigates the influence of media platforms on the public discourse. We find that, in our application, the online and print discourses differ significantly from each other with regard to both the standing of actors and the framing of the main arguments. This variation is on a similar level to the differences between newspaper publishers. Despite this variation, the main structures of the print media and the online media discourses do not differ fundamentally.

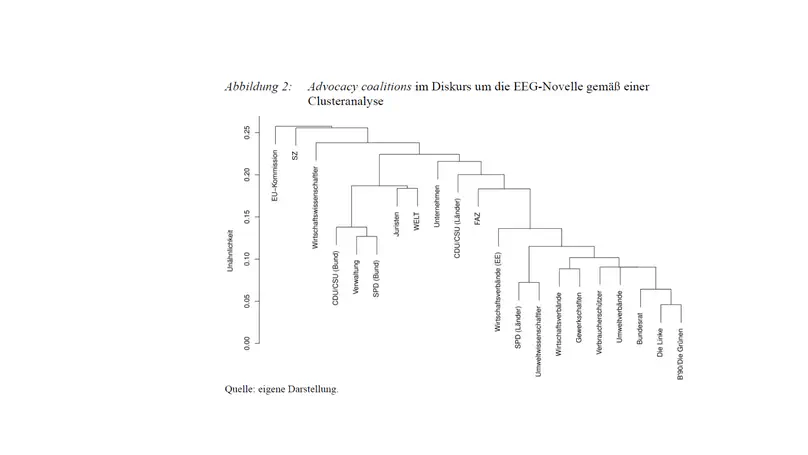

The German Renewable Energy Act (EEG) is an essential pillar of the energy transition in Germany and reveals objectives of the overall German energy policy. This article analyses the public discourse on the German Renewable Energy Act Amendment 2014. This allows us to detect which actors predominantly impact the discussion and which arguments they use. Our main findings are that (i) political parties and institutions dominate the discourse, (ii) the Act is criticized more often than it is defended, (iii) economically framed arguments occur much more often than ecological statements, (iv) in particular, the distributive effects of the amended EEG 2014 are criticized very often and that (v) the government as supporter of the reform is largely isolated and split by internal discussions on its evaluation.